Beyond PPV: Why Likelihood Ratios Matter for AI-Driven Veterinary Diagnostics

Understanding the Critical Difference Between Test Performance and Clinical Utility

As artificial intelligence and machine learning models increasingly enter veterinary practice, clinicians face a familiar challenge in a new form: how do we interpret these tools' performance metrics in ways that actually help our patients?

In previous posts, we've explored the transparency crisis in veterinary AI validation and established frameworks for evaluating different types of AI systems. We saw how clinical prediction models, language generation tools, and imaging AI each require distinct evaluation approaches. Today, we're focusing specifically on clinical prediction models—those AI systems that provide diagnostic classifications or disease probability scores—because they raise unique challenges in translating validation metrics to clinical utility.

While sensitivity and specificity provide valuable insights into test performance, there's one metric that's actively misleading in clinical practice: positive predictive value (PPV).

After nearly three decades working with veterinary diagnostics data, I've seen how the same AI diagnostic tool can be transformative in one practice and nearly useless in another. An AI model that correctly identifies 95% of lymphoma cases in a specialty oncology center might flag so many false positives in general practice that it becomes more hindrance than help. This isn't a failure of the technology—it's the predictable result of how disease prevalence affects positive predictive value (PPV), and why this commonly cited metric is so misleading for clinical decision-making.

The key lies in understanding how prevalence shapes predictive values and why likelihood ratios offer a more stable, practical framework that works alongside sensitivity and specificity for clinical decisions.

This builds on our earlier discussion about the decision-action framework—remember, every AI system exists to influence human decisions. Today, we're diving deep into the mathematical tools that help us make those decisions wisely when using clinical prediction models.

Listen to an AI generated podcast generated from this post

The Sensitivity and Specificity Foundation

Let's start with what works well. Sensitivity and specificity are fundamental performance characteristics that tell us important things about any diagnostic test:

Sensitivity: The proportion of truly diseased animals that test positive (true positive rate)

Answers: "How good is this test at detecting disease when it's present?"

High sensitivity = fewer false negatives = fewer missed cases

Specificity: The proportion of truly healthy animals that test negative (true negative rate)

Answers: "How good is this test at ruling out disease when it's absent?"

High specificity = fewer false positives = fewer unnecessary treatments

These metrics are inherent properties of the test itself. A test that's 90% sensitive and 85% specific will maintain those characteristics whether it's used in a specialty referral hospital or a rural mixed practice. They provide crucial information for understanding what a test can and cannot do.

For example, when evaluating an AI tool for radiographic screening:

High sensitivity tells you it won't miss many cases (good for screening)

High specificity tells you it won't generate excessive false alarms (good for confirmatory testing)

The combination helps you understand the test's fundamental performance envelope

The Fatal Flaw: Why PPV is a Misleading Metric

Here's where things go wrong. Positive predictive value seems like it should be the most clinically relevant metric:

PPV: The proportion of positive tests that are truly positive

Seems to answer: "When this test is positive, what's the probability my patient actually has the disease?"

The problem? PPV isn't a property of the test—it's a property of the test applied to a specific population. And in veterinary medicine, populations vary dramatically.

The Prevalence Trap: Same Test, Wildly Different Results

Consider an AI model for detecting canine dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with excellent performance characteristics:

Sensitivity: 90%

Specificity: 85%

Now watch what happens to PPV in different clinical contexts:

At a cardiology referral center (DCM prevalence ~40%):

PPV: 75%

"When positive, 75% chance of actual DCM"

In general practice (DCM prevalence ~2%):

PPV: 11%

"When positive, only 11% chance of actual DCM"

At a breed-specific screening clinic for Dobermans (DCM prevalence ~60%):

PPV: 87%

"When positive, 87% chance of actual DCM"

Same AI model, same sensitivity, same specificity—but PPV varies from 11% to 87%. This makes PPV essentially meaningless as a reported metric because it only applies to the specific population where it was measured.

The Prevalence Complexity: Why "Population" Isn't Simple

When you're evaluating a patient, what exactly is "the prevalence"? It's not a single number—it's a complex intersection of factors that create increasingly specific sub-populations:

Geographic and Practice Factors

Urban vs. rural (vector-borne disease exposure)

Climate zone (heartworm, fungal diseases)

Practice type (first opinion vs. referral vs. emergency)

Patient Demographics

Age (juvenile vs. geriatric disease patterns)

Breed (Cavaliers with 50%+ mitral valve disease vs. mixed breeds)

Body condition, sex, neuter status

Clinical Presentation

Chief complaint (coughing dog vs. wellness exam)

Duration and progression of signs

Previous medical history

The Diagnostic Cascade Effect Once you've run initial diagnostics, your patient moves into increasingly specific populations. Consider a 10-year-old Labrador with polyuria/polydipsia:

Initial population: "10-year-old Labrador" (Cushing's prevalence ~5-10%)

After finding elevated ALP: "10-year-old Labrador with PU/PD and elevated ALP" (Cushing's prevalence ~30-40%)

After finding poor dexamethasone suppression: "10-year-old Labrador with PU/PD, elevated ALP, and poor dex suppression" (Cushing's prevalence ~70-80%)

Each test result creates a new, more specific population with its own prevalence. Any PPV reported in validation studies becomes irrelevant because your patient is now in a completely different population than the one where PPV was measured.

Why This Makes Reported PPV Dangerous

When an AI company reports "85% PPV," what exactly does that mean for your patient? Without knowing:

The exact validation population characteristics

All the selection factors used

The clinical context of tested animals

Prior test results in those animals

...that number is not just meaningless—it's actively misleading. It creates false confidence or false dismissal based on irrelevant data.

This is why experienced clinicians often ignore reported PPVs entirely and rely on their clinical judgment to estimate disease probability. That clinical intuition accounts for all the prevalence factors that make reported PPV unreliable.

Enter the Likelihood Ratio: The Stable Alternative

Likelihood ratios (LRs) solve this problem by providing prevalence-independent measures of how much a test result changes disease probability:

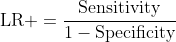

Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+): How much more likely is a positive test in a diseased animal versus a healthy one?

LR+ = Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity)

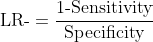

Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-): How much more likely is a negative test in a healthy animal versus a diseased one?

LR- = (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity

For our DCM example:

LR+ = 0.90 / (1 - 0.85) = 6.0

LR- = (1 - 0.90) / 0.85 = 0.12

These values remain constant regardless of where you practice or what type of cases you see. They're true properties of the test, just like sensitivity and specificity.

The Clinical Framework: From Test Result to Decision

Here's how likelihood ratios work in practice:

Start with your pre-test probability (clinical suspicion based on signalment, history, exam)

Apply the likelihood ratio from your test result

Calculate post-test probability to guide decisions

Practical LR interpretation:

For positive results (LR+):

LR+ > 10: Strong evidence for disease

LR+ 5-10: Moderate evidence for disease

LR+ 2-5: Weak evidence for disease

LR+ 1-2: Minimal evidence

For negative results (LR-):

LR- < 0.1: Strong evidence against disease

LR- 0.1-0.2: Moderate evidence against disease

LR- 0.2-0.5: Weak evidence against disease

LR- 0.5-1: Minimal evidence

Why This Framework Complements Sensitivity and Specificity

Rather than replacing sensitivity and specificity, likelihood ratios work with them to provide a complete picture:

Sensitivity and specificity tell you about fundamental test performance:

Can this test detect disease when present?

Can this test rule out disease when absent?

What are the inherent limitations?

Likelihood ratios tell you about clinical utility:

How much does a positive result increase disease probability?

How much does a negative result decrease disease probability?

How useful is this test for decision-making?

Together, they provide both the foundation for understanding test performance and the tools for applying that performance in clinical decisions.

Real-World Application: Multi-Level AI Scoring

Modern AI tools often provide probability scores rather than binary results. Likelihood ratios can be stratified by score ranges:

Example: AI-based radiographic screening for hip dysplasia

Score >0.8: LR+ = 15 (strong evidence for dysplasia)

Score 0.6-0.8: LR+ = 4 (moderate evidence)

Score 0.4-0.6: LR ≈ 1 (uninformative)

Score 0.2-0.4: LR- = 0.3 (moderate evidence against)

Score <0.2: LR- = 0.05 (strong evidence against)

This stratification allows nuanced clinical decisions while avoiding the prevalence trap that makes PPV unreliable.

Case Example: Putting It All Together

A 7-year-old Golden Retriever presents with decreased appetite and mild lethargy. You're considering several differentials, including lymphoma.

Step 1: Estimate your pre-test probability Based on signalment and vague clinical signs:

Your clinical suspicion for lymphoma: ~10% (or 1 in 10 chance)

Step 2: Run an AI-assisted diagnostic test You use an AI tool that analyzes peripheral blood smears for atypical lymphocytes:

The tool has LR+ = 8.0 and LR- = 0.15

Your patient's result: Positive (atypical cells detected)

Step 3: Calculate post-test probability Using the positive result and LR+ = 8.0:

Pre-test odds = 0.10 / (1 - 0.10) = 0.11

Post-test odds = 0.11 × 8.0 = 0.88

Post-test probability = 0.88 / (1 + 0.88) = 47%

Clinical interpretation: The positive test moved your suspicion from 10% to 47%. This moderate probability warrants further investigation—perhaps lymph node aspirates or advanced imaging—but isn't definitive enough for immediate chemotherapy.

Alternative scenario: If the test had been negative Using LR- = 0.15:

Post-test odds = 0.11 × 0.15 = 0.017

Post-test probability = 0.017 / (1 + 0.017) = 1.7%

The negative result would have reduced your suspicion from 10% to 1.7%, likely redirecting your diagnostic efforts toward other differentials.

The key insight: The same test provides different levels of certainty depending on your starting point. If you had started with 50% suspicion (perhaps after finding enlarged lymph nodes), that same positive test would have moved you to 89% certainty—potentially high enough to discuss treatment options with the owner.

Key Insights for Veterinary Practice

🚫 Reject PPV as a decision-making metric: It's only valid in populations identical to the validation study, which virtually never matches your specific clinical context.

📊 Request likelihood ratios from diagnostic companies: They provide stable, clinically useful information that works across different practice settings and patient populations.

🔍 Use sensitivity and specificity to understand test capabilities: They tell you what the test can and cannot do in fundamental terms.

⚖️ Apply likelihood ratios for clinical decisions: They tell you how much test results should change your thinking about specific patients.

📈 Understand your local prevalence patterns: Knowing disease prevalence in your practice helps calibrate all diagnostic interpretations.

🎯 Think in probability shifts: Every test moves you from one probability to another—likelihood ratios quantify that movement.

🔄 Remember the diagnostic cascade: Each result refines which population your patient belongs to, changing the context for subsequent tests.

Conclusion

As AI and machine learning tools proliferate in veterinary medicine, the challenge isn't learning entirely new ways to interpret diagnostics—it's applying the same probabilistic reasoning that underlies all medical decision-making, but with better tools.

Sensitivity and specificity remain valuable for understanding what a test can do. Likelihood ratios provide the missing piece: understanding how much test results should influence your clinical decisions. Together, they create a robust framework for evaluating any diagnostic tool.

The metric to abandon is PPV. It's not that PPV is theoretically wrong—it's that reported PPV values are clinically useless because they apply only to the specific population where they were measured. In the diverse world of veterinary medicine, that population almost certainly doesn't match your patient.

The diagnostic process veterinarians follow every day is already sophisticated probabilistic reasoning. By making these concepts more explicit and providing tools like likelihood ratios that align with clinical thinking, we can help ensure that new diagnostic technologies enhance rather than complicate clinical decision-making.

Whether evaluating an AI algorithm for radiographic interpretation or an ALT elevation on a chemistry panel, the fundamental question remains the same: how does this result change what I know about my patient? Likelihood ratios, working alongside sensitivity and specificity, provide the most reliable framework for answering that question.

This is precisely why my evaluation framework emphasized understanding how AI changes clinical decisions rather than just reporting accuracy metrics. When vendors provide likelihood ratios instead of PPV, they're giving you tools that actually work in your practice, not just in their validation studies.

Technical Appendix: The Math Behind the Magic

For those interested in the calculations:

Converting to post-test probability:

Pre-test odds = Pre-test probability / (1 - Pre-test probability)

Post-test odds = Pre-test odds × Likelihood ratio

Post-test probability = Post-test odds / (1 + Post-test odds)

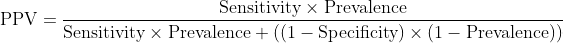

Why PPV fails mathematically:

Notice that prevalence appears twice in this equation. Change prevalence, and PPV changes dramatically, even with identical sensitivity and specificity.

Why likelihood ratios remain stable:

No prevalence term appears in either equation. The values remain constant regardless of the population being tested.

This is a great point about test performance stats, often overlooked. There is a company out there selling an "AI-powered" thermography device that touts its "97% negative predictive value" in ruling out cancer even though the studies that figure comes from used a sample dataset *heavily* skewed towards benign lesions, which will of course make the NPV look better just based on simple math. That was not the only flaw in their studies, but it was a big one.

The post is here:

https://allscience.substack.com/p/can-a-heat-scan-rule-out-cancer